Last year Kazuki Takahashi died.

It was not a good day for me. The night before I finished watching Yu-Gi-Oh GX after many years of watching it intermittently since I was a child. I thought it was a masterpiece, “Dostoevsky for children” as I would later exclaim to friends, and I went to bed completely elated that something like Yu-Gi-Oh existed. Then the next morning I woke up and Kazuki Takahashi had been found dead at sea.

It was the first time a “celebrity” death really felt personal despite this being someone who rarely gave interviews and largely remained a mystery to me. Mostly I was upset that I would never be able to say thank you to someone who unknowingly affected the entire course of my life--I was one of those kids born in the late 1990s who rode out the Cool Japan boom and just kept running with it. In other words: I am one of many people on the earth who has a fascination with the country called Japan, and it was Yu-Gi-Oh that did this to me. I learned Japanese and I now live in Tokyo, Japan, so this became a life-long thing that started with the spiky hair I’m sure captured the attention of plenty of other kids like me. I won’t go too deep into this story because it’s largely personal and uninteresting to anyone who isn’t a close friend, probably--mostly I am trying to say that the anime and manga called Yu-Gi-Oh holds a very large place in my heart and personal history. So I’ve given myself the impossibly large task of deciphering why it does, and what makes this manga about a children’s card game so compelling to my adult psychology.

“A Children’s Card Game”

And yet I had never read the manga in full from start to finish until now at, like, 25 years old because it was too expensive to own in English and now I know Japanese, so whatever. Maybe you’re like me and felt something special in this work, because it was something of a ritual for me to move to Japan and then immediately read all of Yu-Gi-Oh, the same place I first made contact with this country.

Maybe it is because for the story called Yu-Gi-Oh to work you necessarily have to take it very seriously is the reason I am the way I am now. I think I have a tendency to see any work of art as a legitimate expression of the person who made it no matter what kind of idea or setting makes up the core of it--after all, most of my personality is based on a story where a card game decides the fate of the earth; but of course, it’s always more than that.

Yu-Gi-Oh was not always about a card game called Magic & Wizards, nor was it supposed to be. The overwhelming popularity of the two chapter arc led to Duelist Kingdom, and the intense popularity of that led to Battle City. While the anime that was popular in North America had many separate arcs within that feature the card game, the manga itself only has these two major ones.

This article is going to be about Battle City. Everyone who knows anything about Yu-Gi-Oh knows that Battle City is the most interesting and compelling arc of the series. There was never any discussion about this fact, nor was there any need to have one--you could just show your buddy that part where Dark Marik and Dark Bakura have a stupid sexy duel on that airship and they’d have no choice but to agree with you that it was the coolest shit they’d ever seen up until that point in their lives, and it probably still is. But no one would be able to tell you why.

The answer may be as simple as the reason why the duel between Dark Marik and Dark Bakura is evergreen: it’s cool to see cool characters be cool while playing with the same cards you begged your mom to buy for you at Toys R Us, and you feel cool while watching it. But simple coolness alone can’t last for 225 episodes of anime and 38 volumes of manga, so there must naturally be something compelling about these characters and their struggles that keeps your attention.

IN THE CASE OF SETO KAIBA

At first I thought I would do something of a formal literary study of the three principal characters of Battle City (those who hold God Cards), but in the process of taking notes to prepare for this I realized that I had maybe four times the amount of notes written for Kaiba than I did anyone else. I mean, it makes sense: everything about Battle City begins and ends with him, and everyone else is collateral. Sure, he has no interest in ancient Egyptian prophecies and could give a shit about Ishtar family trauma and the spirits of Pharaohs forgotten by history--but that’s precisely what makes him so interesting.

Kaiba is only interested in all this in so far as it gives him power, which is why he agrees to host the tournament at Ishizu’s request in the first place--it means getting his hands on a God Card. Even then, he seizes the tournament as an opportunity to make a break with the memory of his abusive adoptive father Gozaburo Kaiba, former CEO of Kaiba Corporation and at one time the largest military weapons development company on planet earth. It’s an elaborate ploy of his own design to prove himself to be not only the greatest Duelist, but also The Greatest Boy Genius To Ever Live, Period.

All three of these guys--Yugi, Kaiba, and Marik--are trying to make a break with their past and carve a road to the future. They’re all going about it in different ways--Yugi, for example, knows that until the Pharaoh regains his lost memories he has no chance at a future. At the same time he knows that necessarily means the end of their partnership. It scares him as much as it excites him. In Kaiba’s case, though, we’re talking about someone who proudly declares that “I am not bound to the future! The future simply follows the road paved by my footsteps!” A big claim for anyone to make, for sure, but this statement continues to fall apart as he progresses through his own macabre theatre of Getting Over It and realizing his issues are far larger than he ever knew.

Bit by bit unavoidable truths start to plague him. Kaiba can inexplicably read the Hieratic text on the Winged Dragon of Ra--obscure hieroglyphics that are considered arcane even by experts, apparently. Nevertheless, our nonplussed Kaiba goes “that sure is weird,” and simply focuses on how this inexplicable talent can be used to win his card game against Marik. Even when he is literally transported into the world of his ancient inherited memories and witnesses a shared vision with Yugi of their ancestors duking it out thousands of years ago, my man calls it a hallucination brought on by “subliminal messaging” during their duel, and rejects it outright.

We’ve all had our laugh about Kaiba’s insistence on rejecting the blatant mysticism surrounding him, and it’s a shame this behaviour has always been attributed to “funny writing choices” as opposed to deliberate characterization. Kaiba’s goal with Battle City is to defeat his largest rival, win the three most powerful cards through his cunning wit, and then symbolically destroy the memory of his abusive adoptive father through the destruction of the island the tournament finals are held on. That’s why if he even begins to accept the larger plot happening around him, it would threaten not only the basis of all his achievements as an individual, but the story he’s written himself to be the protagonist of.

But he knows this is a flawed way of going about it, and there are two key reasons why. The first is that he lost his duel against Yugi, which should’ve been the punctuation on his epic plot to overcome himself. Not only does he lose, but he loses because his master combo to summon all dragon-type cards in both players hands meant the Red Eyes Black Dragon that Jonouchi entrusted Yugi as a symbol of their bond was also summoned and completely changed the course of that duel. Here he sees what he’s lacking: friendship. Maybe he’s a little lonely, maybe it gives him a moment of pause, and maybe I can write as many asides about what I think goes on inside Seto Kaiba’s brain between panels, but that would be besides the point. The fact of the matter is that he never once accepted he could lose, or that the past and the future wouldn’t coalesce as perfectly as he had written it.

The second reason is that he sees what happens to Marik. Once Rishid is defeated and Marik’s alternate personality comes out, the ugly truth that Marik himself is responsible for his father’s murder also rises to the surface. Ishizu claims this alternate personality was born out of Marik’s “anger and hatred” (怒りと憎しみ), the same words Kaiba uses to describe as his sole motivating factor, that “anger and hatred” has given him everything he has. Yugi again turns these words against him to describe the flaws in Kaiba’s future he’s written for himself: that because it is born of his anger and hatred, it will only lead to more anger and hatred. Marik’s alternate personality says it himself: he is only interested in destruction (破壊), the exact same thing Gozaburo Kaiba was after. Kaiba observes this possible future for himself, where Marik has literally tricked himself into believing a story he made up, and for the first time since the beginning of the tournament asks himself why he decided to organize this in the first place.

We never fully see Kaiba accept his place in the Egyptian background that surrounds him, but we do see him begin to. When Yugi does inevitably defeat Marik with two cards Kaiba gave him, he starts to see the value in Yugi’s way of living and ultimately decides to forgo any sort of thinking about his past and simply accept who he is now, taking off to America with Mokuba to set up Disneyland or whatever. It’s only through understanding his helplessness in ever understanding either his past or his future that he becomes comfortable with both and finds the way forward he was looking for in the first place.

This decision is reassured as positive in the following arc when we actually do get to see the story of his Ancient Egyptian ancestor, who also did not know his father and was tempted to evildoing as a result. What Seto Kaiba has that Set doesn’t is being physically separated from his past. In Japan, there’s no need to play out any tragedies but the ones you write for yourself, just like he has with Battle City. Akhenaden, Set’s father, is literally doing dealings with Zorc Necrophades, god of all things evil and dark, an inescapable force of power that he has no choice but to deal with, and cannot possibly defeat. Gozaburo Kaiba, meanwhile, is mortal--and dead, no less. The only thing left for Kaiba is the battle within himself against his past, and he expresses this by organizing Battle City.

The point is: Battle City is about the past. Because without the past there is no future.

So what is it that I’m getting at here? What are the words you came here to read? I’ve deliberately shied away from writing certain terms and phrases here thus far because it seems like the moment I write them someone may groan, or that this tab will be closed. But that’s precisely why I know this is the reason I set out to write this is to finally verbalize to myself what it is about Yu-Gi-Oh that I haven’t been able to get over for 25 years. It’s been on my mind since Takahashi’s death last year, and I still don’t think I’ll have enough words here to say exactly what it is I want to say. It feels like if I write them, if I commit to this reading of Yu-Gi-Oh, I might find out something uncomfortable about myself and my identity.

There’s one other character I have to necessarily write about before I can write those words I’m scared of, largely because the second I write them it’ll make or break whether or not you give a shit about whatever it is I have to say here.

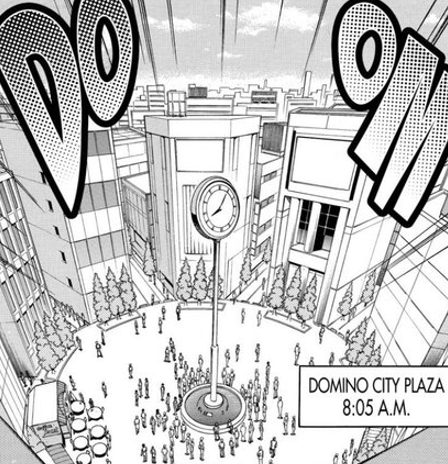

Domino City

Yes, the city! It is as much of a character in Battle City as anything else. Domino is the perfect “nowhere” town--in the English version of the anime its location was deliberately obscured in favour of making it “marketable,” but in the manga it’s always clear that Domino City is a fictional metropolis that exists in Japan. It’s an undefined place--we don’t know where in Japan it is, much like we don’t know where in America Bandit Keith hails from (despite speaking far better Japanese than Pegasus, a fellow American). National identities in Yu-Gi-Oh go up in the air like this in favour of archetypal depictions of countries and places--the geographic vagueness of Domino City is its greatest feature.

Even now I can clearly remember where duels took place: even the first Rare Hunter sipping an espresso at a cafe sticks out in my mind, which is odd that it should considering Duelist Kingdom had environmental tactics built into its duels yet the island itself is nowhere near as memorable. Kaiba and Yugi team up on top of a skyscraper set to blow, an aquarium duel a quaint reminder of the unnaturalness of city life, the buildings towering over every panel, every speech bubble, every page. Every alleyway of Domino City becomes a battleground, every street an opportunity for a duel, every pedestrian an opponent you haven’t met yet.

The characters run through these streets looking for their destinies. The phantom of Ancient Egypt can barely be seen through the half light of a streetlamp, and beyond it the cloaked figures of Ghouls who stand in your way, equally a symbol of the encroaching past as they are dedicated to concealing it from you. Lightning strikes and the earth rumbles--someone has just come face-to-face with themselves in the form of a bright red dragon on a trading card. It’s too late to even consider what it means, because your best friend is about to drown in the bay. The mania of those dragged in by the spectacle of it, as much actors as they are victims of another’s theatre. Dreams of the desert, the blazing sun, and the unknown future collide among Duelists. The clock counts down destiny, and the sun sets on the past. Beneath it all--an ancient prophetic slab in a museum begging to be solved, and a promise made between two friends that transcends all of this.

This is Domino City.

I grew up in the largest city in Canada: Toronto, Ontario. I also played Magic & Wizards in said city, both as a child and as a high schooler (but after I heard about Pendulum Summoning, I threw my hands up and decided my puny Lightsworn deck stood no chance against it). Anyway, here is some additional information necessary about me: my parents immigrated to Canada from Turkey, and I was born as a first generation Turkish-Canadian. I am also shockingly white--most people don’t believe me when they hear I’m completely and utterly ethnically Turkish. The point is I didn’t look too different from my white Canadian classmates, but the inside of my home and the outside city were two different worlds to me. Most importantly: my parents made it their mission to remind me how my life is the direct result of a bunch of people mucking around in the desert for a few hundred years and now I get to play with Yu-Gi-Oh cards in some insane chain of causality that I could not even begin to comprehend. That’s why it was always easier to understand my own heritage as a kind of prophecy, and the thing that helped me understand it this way was Battle City.

Kotaku has a great article that was published around the time Takahashi died about the importance of Yu-Gi-Oh among children of immigrants, and how it became a kind of shared language that cast aside ethnic and cultural origins. It goes on to say that this was because in the show, all “outcasts” used Magic & Wizards to transcend whatever societal and cultural factors held them back. It’s a cute piece about the position of Yu-Gi-Oh in immigrant communities, but it doesn’t address why it had such a hold to begin with.

The most effective thing Battle City does for the immigrant child, I think, is that it shows an ancient prophecy unfold against the backdrop of an archetypal city. That the city itself becomes a kind of battlefield, I’m sure that general concept is not unfamiliar to immigrant children. Japanese stories where an ancient samurai prophecy unfolds in the present day are about a dime a dozen, so what makes Yu-Gi-Oh special is that it is a Middle Eastern prophecy (not even a European one!). To see these characters struggle to understand their distinctly brown origins while looking around their homogenous city halfway across the world--well, it was a bit familiar to me, and I’m sure it was to others.

That’s why it was so crucial that I took a long hard look at Seto Kaiba, who has the privilege of writing his own personal story just like I did by hiding behind my blinding whiteness. I carved a path through my own fractured identity and found myself here in Tokyo, Japan. It’s no accident that I made all the effort to remove myself from the city I grew up in and place myself in another one a whole ocean, culture, and language away from my own, maybe in my own personal attempt to rewrite my history to contextualize my future. It’s also entirely possible I did this to avoid dealing with the issue at hand: those two words I haven’t been able to say until right now.

Okay, let’s move on with it: Battle City is about generational trauma.

But not really--this is what I expected I would have to say before I read the manga, and this is what I wanted to write about, but I forgot the act of writing even if it isn’t fiction is always a transformative and revealing experience that takes you places you didn’t expect. Oops!

In light of this expectation I equally expected to have many, many thoughts about Marik, but clearly I walked away with an even greater appreciation for Kaiba than I had before. I was afraid of Marik because of how brutally his past is depicted, and how that brutality reflects my own understanding of the background I come from now as an adult. I am at that age where the actions of your parents and grandparents and so on become more palpable to you, and I can begin to interpret their stories as a larger narrative that led to my own birth. So I felt that the despair Marik feels at his own past, the way he deals with it, and the way it concludes might have been conducive to the still ongoing process of understanding my own history.

But when I was a child I had no such understanding, and I had no real personal interest in the country my parents came from, nor did I really have the capacity to care on account of being a child. That’s why it was easier for me now to read Yu-Gi-Oh through Kaiba’s perspective, and Marik’s character became nothing more than a thought experiment to read in relation to Kaiba. I was very prepared to come to terms with however it is my life is shaped by my own family’s history, but in reality I simply found myself as lost as I have always been.

I even thought about putting those two words in the title of this post, as I expected to write some sobbing bereavement of a sociopolitical Turkish drama I can’t understand and tie it back to this manga about a card game. To that end while writing this I tried to look for any other writing about Yu-Gi-Oh in relation to generational trauma, immigrant stories, and just the accounts of those who had a close relationship with it in general, but nothing really came up. It was a little lonely realizing I may be the only person who puts this much stock into the manga about a card game deciding the fate of the earth, but then, maybe I’m just saying what everyone else feels might be a little too silly to say: that Yu-Gi-Oh is about having the courage to be exactly who you were born to be.

Of course, generational trauma is a part of that for many people. But thanks to in-jokes and memes, we’ve reduced the facts about Yu-Gi-Oh’s plot and themes to nothing more than set up for punchlines. For example: in Yu-Gi-Oh The Abridged Series, a gag that persists all throughout is Yugi shouting “puberty!” when he transforms into the Pharaoh, and I think many of us internalized that it was always a metaphor about that--about growing up. But “growing up” means a lot of things, and the presence of an ideal self that manifests in times when you’re too weak to deal with the situation at hand is something far more complicated than simply saying your balls dropped.

It seems like the only way many adults in the west who grew up with Yu-Gi-Oh are only capable of talking about it now through commenting on its many absurdities. It’s like they have to justify their passing interest in it by constantly reminding us they know how silly a premise it is, because to give it any more importance than that would maybe indicate that you take a whacky show about a children’s card game too seriously. Perhaps you too, reader, are starting to grimace at this post because I’m also taking a whacky show about a children’s card game too seriously.

The fact of the matter is that Yu-Gi-Oh spoke to you, probably, since you clicked this post and had even a remote interest in what I had to say about it. It is undeniable that there are certain themes and ideas that meant something to a child, and that’s exactly who they’re meant for: children. Of course, you, the so-called reasonable and rational adult that enjoys finer, more nuanced works of art than Yu-Gi-Oh may find some of the surface level appearances of it trite and over-developed, but it was written that way to make these large and complicated ideas palpable to children. In that sense, Yu-Gi-Oh is a major accomplishment.

My life changed because I found Yu-Gi-Oh when I was a child. It gave me a way to contextualize my identity in a world that is hard enough to navigate even with a stabler foothold on your own understanding of where you came from. I realize this now as an adult because I have the words to describe these parts of myself, and I see those words reflected in the characters of Yu-Gi-Oh. Maybe I did see these themes as a child, and maybe I didn’t--the fact of the matter is I see it now, and I retroactively apply this to the past. These readings and experiences coexist with each other and form who I am now, and I can’t deny that.

It may also be that I’m writing this at all to reframe the position of Yu-Gi-Oh in my life and its circumstances I’ve created as an adult, particularly the fact that I now live and participate in Japanese society. It was always the origin point in my “Japan story,” which is the story every foreigner living here has about how they arrived in this country. I usually joke and say “I saw Yugi’s spiky hair at age 6 and now here I am,” which is basically true. But while Yu-Gi-Oh held a place in my Japan story, I never considered exactly how it all relates back to my life story. Why did a Japanese story about a middle eastern prophecy unfolding in an urban space across the world inspire me to force myself into this corner of the world? What was it exactly that was transmitted to me when I watched Seto Kaiba deny his brown roots and devote his life to games? The answers to all these things are revealed to me through the circumstances of my life as they are now, as they are irrevocably linked to my experience and reading of Yu-Gi-Oh. So the conclusion I can draw here is pretty banal: that Battle City is only as interesting as however marred you are by your own immigrant experience, which may or may not be coloured by an obsessive interest in all things Japanese.

Really, what I feel like I’ve ended up doing here is emulating Kaiba’s actions even further by preparing a pre-written script for what I perceive my past to be and how it relates to my future. In truth, I’m just as lost as he was at the end of Battle City. I rewrote this post so many times to try and seek out whatever it is I feel about Yu-Gi-Oh, but I’m beginning to realize that this feeling itself is the most important thing I gained from it. I still don’t know the direction my story is going, and I probably never will--but I’m comfortable with where it is now, and I have only Yu-Gi-Oh to thank for that. I expected to solve my own Millennium Puzzle, but that isn’t something you can do in a fortnight.

I will never find the words to say exactly what it is I feel about Yu-Gi-Oh, but for now this will do. What I may have been most upset about when I found out Kazuki Takahashi had died was not that I couldn’t say thank you, but that even if I could, I wouldn’t have been able to express in words what exactly it is I was thanking him for. I’m sorry if you came here expecting some analysis of duels as expressions of their duelists, or metatextual observations between the card game as it appears in the manga versus how it’s played in real life. If anything, I hope maybe I’ve communicated even a semblance of why I feel an immeasurable weight in my chest when I read a manga about a children’s card game.

A final aside: the reason Yu-Gi-Oh has an Egyptian background setting to it is because at the time of its writing all archaeological findings pointed to the origin of the history of games being Ancient Egypt, so it was decided Yu-Gi-Oh would be about the lost soul of an ancient Egyptian Pharoah. But more recent archaeological research has provided new artifacts--the oldest game pieces known to man were in fact found in Turkey. So if Yu-Gi-Oh had been written ten years later there may have been a small chance that the Millennium Puzzle’s signature eye symbol would have been that of the Turkish evil eye, and Pharaoh Atem would’ve been Sultan Ahmet, and this series would’ve been even more precious to me than it is now. But that is precisely what makes Yu-Gi-Oh so interesting--that it speaks to the pharaoh, sultan, and king within us all. Like Jonouchi says to Yugi in the first chapter--”what can be seen without seeing” is to me the unforeseeable future and the everpresent spectre of the past that colours my every action. Or maybe it’s just a silly show about a children’s card game--it’s all there if you want it to be.

March 31st, 2023