“I don’t know. I really don’t know anything anymore. It feels like I took everything for granted, like I was living in a contradiction. This whole thing we call existence is starting to fall apart at the seams for me--seriously, not to sound like a first year philosophy student here but why the fuck am I alive? On the airplane back from Toronto I started to freak out in my seat. How are we just accepting this for what it is? How the hell has our civilization been around this long and we haven’t put all our energies to solving this mystery? The fact that we can dream up a concept called ‘mystery’ speaks to the absurdity of it all, like the universe itself is tempting us. But that’s exactly it--it all feels so by design and full of intent that it’s like this cosmic joke happening to me and only me. The world is like this riddle I have to unravel as part of this journey to self-actualization or whatever psychiatrists or gnostics and so on want to call it. You always seem to know exactly what’s going on, or rather there’s a complete commitment to the bit we call ‘living’ I can’t get a hang of. How are you okay with this?”

She sighs and sips the Viennese coffee in front of her; the cream leaves a mark on her upper lip that she wipes away with a napkin. There are tears in my eyes and it’s 3pm on a weekday, broad daylight. The people sitting next to us are talking about applying for a loan. She looks at me with a very careful gaze, trying to find a balance between realism and kindness--or at least, I think she is.

“I just don’t worry about things like this anymore. Have you ever even had anyone near you die, let alone been present for it? I saw my grandmother die, and I don’t mean just the passing. I mean the period leading up to her death I was constantly with her, and it was like she had died long before the actual moment of her death. Watching this process play out in my house, I’ve never forgotten it down to its smell. That, and...” she looks off somewhere and then continues, “actually, let’s go somewhere.”

We leave the cafe and she leads me through the Motomachi shopping district here in Kobe. We walk in the Book Off and she scans the shelves until she finds what she’s looking for, and she hands it to me so matter-of-factly that it already feels like an answer.

“Here. I read this when I was in 4th grade and it kind of solved all these things you’re crying about. I don’t worry the same way, or rather, I’ve never worried about it all before because it convinced me of many different things. I’m not saying you should read the whole thing or to take it at anything more than face value, but it might be of some help.”

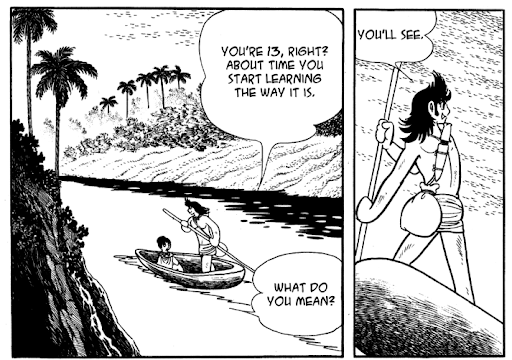

The book is Osamu Tezuka’s Buddha.

---

Some thousands of years ago someone who may have been named Siddartha wandered South Asia and had figured out a truth you and I continue to struggle with thousands of years later. The exact dates and details of his life are unknown, but he need not have existed at all--the only important takeaway here is that the same questions have been asked forever, and no answers have ever been given except for the ones we find in ourselves.

In high school I had a habit of seeing how far I could walk in any direction and still make it back in time for my next class during my lunch break. I would eat something I could hold in my hands and usually walk either towards the ravines that cut through the neighbourhood or head as far downtown as I could before the train ride back would get too long, usually about three stops. I would listen to music I thought made me better than my peers, think things about the world I felt to be absolute truths, and couldn’t wait to get home to my real life on the computer. The questions of why I exist or where I go after I die do not enter my head, because I’m immortal at this age like any other teenager is. The only thing Siddartha and I have in common is that we both wander and feel a certain way about the world.

The TTC rushes by on the tracks next to me between Davisville and St. Clair, and I feel completely righteous about the world and my position in it because I know one day I will get my turn. In reality I had nothing to feel so high-and-mighty about because I was just a scared little teenager hiding behind delusions of grandeur to the tune of, like, Vampire Weekend.

I didn’t know anything at all.

In my high school’s library there was only one manga, and this always pissed me off. The manga was Osamu Tezuka’s Buddha, and they were so pristine it was as if no kid had ever laid hands on them. I’d flip through it every now and then and wonder: who the hell is reading this? It’s just bald guys in robes trekking mountains and shit. Why’s this the only damn thing available to read in this whole school? Where’s Prince of Tennis? Shaman King? I’ll even take a look at Fushigi Yuugi if I have to. What kind of guy sits down and reads Buddha?

Here it is: I am now the guy who reads Buddha.

---

At the guesthouse I’m staying in the guy sleeping to my diagonal is coughing up what sounds like a new coronavirus, but I can barely hear it because I’m already in tears over the first 20 pages of the damn thing. A dying traveller is aided by local animals--a bear brings fish from the river, a fox some grapes. The lowly rabbit searches and searches but can’t find anything to offer to the traveller. The traveller finds the strength to make a fire, and then the rabbit tosses itself inside to offer the only thing it can: its flesh, and its life with it.

I don’t know. The laws of the world as it appears in these twenty pages of a comic book are almost painful to read, so undeniably sharp and pointy. I can’t understand the rabbit’s sacrifice at a personal level, but I understand it in a way that I can’t put into words either--I just don’t know.

What am I even doing here? I don’t live in Kobe, and I basically forced her to come out and see me on account of my existential dread. I don’t know--a lot of things compounded at once. I went back to Canada for the holidays and helped my parents move which included throwing out so many menial things that I once scribbled on at various different stages of my life--old notebooks, math homework with characters drawn into the margins I’ve long since forgotten the names of, that kind of thing. I sold off what little possessions I had left for “safekeeping.” There’s no trace of me left in Toronto, Canada, except for the memories in the handful of people I call friends. My parents, older by the minute, are also parting ways with half of their lifetime worth of material possessions in a kind of downsizing as they enter the winter of their lives. It’s sad to see those ugly chairs go, but we all enter this world with nothing and leave with nothing.

When I get back to Tokyo I fall into a kind of paralysis. The only thing that gets me out of bed is the need to use the bathroom, and the paltry momentum from that carries me to the kitchen to make the bare minimum of food. I’m losing weight, I can barely form a thought, and going outside freaks me out. I’m going to die--fuck! Which necessarily means: I’m alive--fuck! I feel awkward and uneasy, but these emotions in and of themselves scare me too. The bed begins to eat me alive, and I realize I may as well already be dead.

So I called up the one person in this country who anchors me to my own existence and I know will not judge my almost foolishly simple worries, no matter how large or small. I selfishly ask if she can meet the same day and get on the bullet train bound for Kobe with the tiniest bit of luggage, unsure of how long I will be away or how far I will go. I just know I need to be in a situation where I’m forced to make decisions every second of the day, or I’ll lose to these feelings keeping me bound to my bed.

---

“I feel like I’ve lost some kind of innocence.”

“Trust me, you’re almost too innocent.”

The karaoke box is playing advertisements on loop. I’ve just sung Patricia by The Pillows in an attempt to feel normal, but the tears start again. There’s an image of a young boy in a void inside me, and when I look closer at him it’s my younger self, a high school student with a grudge against the world.

“I don’t think I can even sing this song anymore. It feels like I’m not allowed to or something.”

“Come on, you’re fine. The song is the same, it’s just the way you feel now.”

“I don’t know about that. I think something inside me is different, like for the first time ever I know I’m going to die.”

“We all are.”

“That’s what scares me, though. Doesn’t it scare you?”

“I just don’t want it to be painful.”

“I don’t even know how to think about it, let alone feel...”

“This is part of it.”

“Thanks for being there for me.”

“You’ll be okay. I say that with full confidence. You wouldn’t be here right now if you didn’t already have the answer inside you.”

“You think so?”

“I know so. It’s only natural you’ll feel like this sometimes, because you’re doing something that’s necessarily scary. You miss your parents, don’t you?

“All the time.”

“And yet you’re still here. Don’t you see that even this basic fact shows you live in such a way that you’ve already made a decision about life and death? You should be more proud of yourself, not many people can do what you do.”

“Maybe, but I’m still so scared.”

“We all are. But at least we’re in it together.”

---

The next day I make my way over to Kyoto for no real reason other than it feels like a waste to come to Kansai and not see it. I call up a friend living in Osaka and summon him to Sanjo, and he’s as shocked to see me as I am to be there. I explain the situation at hand to him and he agrees to drink our body weights in beer--it’s Friday night, after all.

“So you’ve lost the plot?”

“I’ve lost the plot as they say, yes.”

“What comes now?”

“It really doesn’t concern me.”

“Then shouldn’t you be happy?”

I guess I should be.

By midnight he tells me he has to go back home to get the rest necessary for his date tomorrow, even if we’ve had enough alcohol to put us to bed for the rest of the weekend. I toss him into a taxi and continue my rampage through Kyoto’s carefully lit night, like some kind of demented existential version of Night is Short Walk on Girl that is nowhere near as cute and endearing. I scour Instagram for something to do and realize a Tokyo-favourite band I like is playing some club at 2am, and I mosey on over by the river. They tear the roof off the place, and when I say hi afterward they’re all shocked to see me--”we are in Kyoto, right?” I laugh, but honestly I’m not sure what I said to them or anyone else there. The next thing I know I’m calling everyone I hold dear in some desperate attempt to feel connected to the ground beneath my feet again.

It’s probably around 4am now and I’m standing in the warmth of a Family Mart calling someone who probably doesn’t want to hear from me, and eventually the staff member works up the courage to tell me to go home. I beg and plead with him, appealing to his humanity, but he refuses.

Then I wake up in my tiny bunk in the hostel and I peer at the sunrise through my tiny window, where Buddha waits for me on the sill. On my phone the last communication I had with a person is this:

Good luck out there, they say.

Trying my best, I’ve written back.

All you can do, they say.

It really is all I can do.

I am decidedly too hungover to go anywhere else so I decide to spend another 24 hours recovering in Kyoto. As I walk by the Kamo River I remember what it felt like the first time I came here many lifetimes ago when I was still a lowly lifeform that we call “tourist” in human tongues. Kyoto is one such town overrun by these creatures, but now and again I feel the same thing I did the very first time I stepped foot in Tokyo: my own presence, traces of myself yet to come, the future ahead of me.

18 years old, a random crosswalk in Shinjuku. The sun is setting and the streets are beginning to darken. Everything is a shade of purple as night steps foot into Tokyo. It’s my first time travelling alone and really, the first time I am ever truly alone in my life. As I look at the sliver of sun over the metropolitan building, I feel something move into place inside me. Despite everything you’ve read in this blog I never had the mania of wanting to move to Japan growing up, but as I cross the street here it seems like something I might really want to do. For now, though, I am 18--there’s nothing to do but exist, which I am trying my best at.

Siddartha timidly wanders outside the castle grounds of Kapilavastu where he meets wandering Tatta. He’s brutish and violent but Siddartha can’t deny he envies that Tatta lives true to his nature. Tatta isn’t ashamed either and is kind to the prince who has yet to let go of his worldly possessions and connections and become the person they still call Buddha, the awakened one. To this Siddartha the world is still an unknown, terrifying void that exists beyond his fantasies.

---

Again in high school I bite into my Whopper Wednesday special. Suddenly I feel strange and weird and am deaf to the conversation my friends are having about whether Goku could defeat Luffy. In my hands is a deliciously cheap Whopper, but there’s also a bit of a cow that died to be there. Wow, I think to myself, what an annoyingly obvious and somehow pretentious thought to have. Then I tell my friends Goku could definitely kill Luffy.

Hundreds of billions of years later the particles that make me intermingle at the end of everything, now unrecognizable from the body and concepts that once made the person who wrote this post that’s probably long turned to dust, along with the earth, stars, and everything in between. No one remembers the person who may or may not have been called Siddartha, nor do they remember Buddha and even less so a human called Osamu Tezuka, because there are no people left to begin with. Everything is still and quiet in our corner of the universe, and I float towards oblivion completely unbeknownst to myself.

The burger tastes good again this week.

--

The taxi driver tells me he can’t take me straight to my accommodation because it is “physically impossible.” I’m still groggy from the early morning train ride from Kyoto to Onomichi, and I have no idea what he means.

“What? Physically impossible?”

“Physically impossible.”

“What exactly does that mean?”

“It’s only accessible by foot, up that staircase.” He gestures to the seemingly never-ending staircase to the left of where he’s parked the car.

“Can’t you just, like, go around? Like to the top?”

“No, I can’t.”

“So I have to climb?”

“Yessir.”

I look out the window and notice it’s still raining. I give the old man driving the car a kind of pleading face, but neither of us can really do anything here. I pay him his 700 yen and start lugging my suitcase up the--and I swear to god this is true--300 steps.

I chose the location because it had a good view, but the accommodation notes on its website that because the building is 100 years old it has no modern affordances, including sound proofing. “We kindly ask those who are light sleepers to reconsider,” says the Rakuten Travel page, but there was nothing about the goddamn steps.

I get there and the host who comes to greet me can tell I’m exhausted. He tells me there’s a parking lot less than a few metres away accessible by car if you go the long way. At this point I realize I’ve left my phone in the damn taxi.

While the host is phoning the cab company and trying to do a kind of reverse engineering on which cab I rode, I’m looking at a paper map of the city trying to make sense of Onomichi as fast as possible. The host comes over and points out an area by the water where people “hang out,” but when I actually make the trek down there it’s basically old people shuffling between a few establishments in a shopping district. I try to find a place to eat dinner, and I turn a corner to discover a small sign that says they serve “small plates.” Google Maps reveals this means you pay an old man a set amount of cash and he brings out whatever he likes--the best kind of restaurant there is.

When I walk in he immediately jumps in his seat, and I tell him I’m alone.

“Japanese OK?”

“Yes, I can speak it just fine.”

“Oh, phew.” He explains he always turns away foreigners because it’s too much hassle to cross the language barrier. He timidly pours me a glass of beer, then compliments me on my Japanese. We do the usual song and dance--where are you from? Canada. Wow! What do you think of Trump? Bad guy, eh. You sure said it. How about that Greenland business? Greenland, yeah. Rough stuff.

And so on.

“What brings you to Onomichi?”

“I don’t know.” I’m too embarrassed to say I first heard about it in Yakuza 6 for the Playstation 4 and figured I should visit the real thing someday.

“And yet here you walked into my shop. I’m a little moved.”

“I picked it based on the sign alone; it’s got good design sense.”

“That old thing?”

“I guess I chose it because it looks old.” We both laugh.

“You like that kind of retro thing?”

“I don’t know if I would call it retro, but more like a leftover from an older world.”

“Which older world are you from?”

“I’m 27, so 1997. I can still remember the analog world before it turned into this.”

“27! I thought you were older than that. Not because you look old, just the way you feel.”

“I get that a lot.”

The conversation goes through variations of this topic. He doesn’t like the digital world and only accepts cash, even if people beg him to use PayPay. Just can’t figure it out, he says, why should I have to learn all this extra stuff when paper’s been just fine since the beginning of time? He tells me he’s born the same year as my grandfather, and is in his early 80s. He has a granddaughter only a little older than me with four kids of her own, which makes him a great grandfather. Then he asks me what I’m doing in Onomichi again, and it all comes out.

“I don’t know. I think I just got scared of dying and all that, and I got on the train.”

“Ah, yeah. That happens to us all. My own dad passed when he was 80, and now that I’m his age it really makes me sweat sometimes. But I tell you what, ever since I became a grandfather I stopped worrying about that kind of thing. When I saw the faces of my grandkids, death or whatever didn’t even enter my mind. Then they grew up and became adults of their own, and when I see my great grandchildren I feel it all over again. The answer is probably in there somewhere.”

“I’ve started to think so too,” but I’m too embarrassed to say this is because I had recently watched Victory Gundam where this topic of children is discussed in a way that made sense to my psychology that seems to only respond to robot anime.

“But you’re here, and you’re doing your best, aren’t you? We’re having a conversation right now, aren’t we? That’s so funny to me, that a foreigner like you can walk in here and understand an old man like mine’s Japanese.”

“I just think I had a little too much free time and ended up studying more than I should’ve.”

“Come on, don’t be modest.” He pours me some more beer. “To tell you the truth, moments like this feel the same as looking at my grandkids. When I see someone trying his best to understand his fellow human, it brings me a kind of hope for this country, which I guess is what I feel when I see my grandkids too. The future and all that--I see it right there on your face.”

“I don’t know...”

“But you do know. You came here today, didn’t you? You walked into my store, and we had a good conversation like this. There’s something in you that still moves your feet and makes you want to eat good food in stores with ugly signs and old farts like me keeping shop. Isn’t that enough?”

I just smile at him, and I think of my own grandfather. Does he think these things when he looks at me? I feel guilty that I’m so far away from him, depriving him of that feeling. I just can’t understand how Siddartha abandoned his family and people in the name of saving humanity from itself, but then maybe that makes him just like the self-immolating rabbit.

When I get up to pay I ask if he takes PayPay, and then we both laugh. At the door we look at each other one more time and he tells me:

“Do your best, kid.”

There was such a warmth in his eyes that I couldn’t think of what to say for a second, and then all sorts of half-finished thoughts wiggled their way out of my mouth.

“I will, because I like it here. I want to do my best both for me and for your great grandkids and all the kids in the world. I promise I will, I really do.”

He shook my hand for a really long time. We never asked each other our names.

--

The Seto Inland Sea is so black it might as well not be there. A ship sounds its horn in the distance.

I don’t know. I really don’t know anything anymore. I take it all for granted, the same way anyone does, because we don’t know any better. The whole world is just this self-actualizing truth, and maybe even writing something as simple as this will make you roll your eyes--but you don’t know either, and it’s irresponsible to pretend you do. Then I look at the old man’s face, and it seems so eternal and matter-of-fact. It’s almost like he’s always been this old, and even when I’m his age I won’t feel as old as him, the same way I hardly feel the age I am now. Everything in the world feels that way, like it’s always been there and always will be, even though we know without a shadow of a doubt that this isn’t true. There are so many contingencies, so many kill scenarios, the most pressing being whether or not the sun will rise again tomorrow.

“But it always fucking does,” my friend back in Toronto told me when I voiced these worries to her. So much comfort in her throwaway comment, because yes, of course it does.

In the distant past, my father comes back from his studies in the US. There’s no internet, no easy way of getting in contact with anyone, and so returning to Turkey feels as fresh a start as moving to Japan. There’s a cruel emptiness to it: the same places, the same people, but something is definitely different. Time has perceptibly left a mark on this spot while he was away, and now it can’t necessarily be called home.

He wanders the streets to find meaning in it all. A newly-graduated engineer can find work, but whether that work is rewarding and well-paying is another issue, even if it is the 1980s. Life goes on anyway and he makes the most of it: taking on jobs where he can find them until finally settling into something cushier, meeting the right woman, being in the right social circles.

Beyond chance moments like that is simple and pure determination to find a meaning in it all. What was the point of going to the US if all it led to was this emptiness? That can’t be correct, since studying there was so full of meaning and hope. My father at this point in time is a young man, younger than I am now, and these questions I struggle with now come bursting forth, the same way they must’ve for Siddartha all those years ago.

My father at that age can barely imagine a wife, let alone a son who will wander to a corner of the earth that he can’t even picture. Japan is somewhere that only exists as a concept, a word that follows these other two: “Made in.” To my father who is yet to be a father, there is nothing but the simple act of finding meaning and that in itself will handle the rest.

But I’ve only ever known him as my dad, and he will always only ever be my dad. The pictures of my dad as a young man make me feel like Hamlet gazing at poor Yorick--someone who once existed, but is no longer anywhere to be found. Ah, man, if I’m making Hamlet allusions things are probably getting real bad for me.

I wander through the pitch black night of the Seto Inland Sea back up the dimly lit stairs, and take a detour through a graveyard on the way up. A statue of some Boddhisatva or the other has caught my eye, and I take a good look at his face. I’ve never been a religious person, and this is probably like that scene in Home Alone where he runs off to the church for some kind of safety in the middle of the night. Or maybe it’s like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off where he’s staring at the painting for so long it changes him profoundly. Or maybe I’m just trying to recreate some movie moment in an effort to feel that profound connection to all things Siddartha talks about.

All I can really think about is my dad, who is half the reason I’m here at all. How did he ever feel like he knew enough to bring someone else here? How did he ever feel okay with it all? When I called him a week before this trip he tells me that it’s just a matter of setting goals and surpassing them. And then one day, he says, there’ll be nothing left to do, and you’ll be fine with it. That’s life, man.

In the photos he looks so happy. I hope one day I will be too.

---

The Brahman tells Siddartha that all living beings, not just humans or animals but plants and so on too all come from the same source of life, to which we will all eventually return. The particles that made up our bodies will be recycled into the universe, our energies converted for those that inherit our earth. Nature, the universe, and reality itself is us and we are it--so says Siddartha’s vision of a naked moustached old man.

I noticed while writing this that I started to cut things out of my trip that I deemed “irrelevant,” but to what? This was always intended to be the last post of this blog in the form it is now, because I noticed I was already writing a lot of the same things over and over. But how do you conclude something that necessarily has no closure? The subject matter is my life, after all, and I’m still alive. Maybe this need for closure is what put this existential dread in me in the first place, because the next natural line of thought it brings you to is dying. If I’m being selective about what parts of my life are meaningful enough to be committed to text and which can just be for me, then I think this entire project is a contradiction.

The short of it is this: I made valuable connections with all sorts of people in about two weeks while taking various trains across Japan. I learned many things about myself that maybe some people find out much younger and much simpler than I did. I even contacted some of those people about using their actual names and occupations and so on in this post, which they graciously agreed to. But the more I think about this the more I realize: those are for me and me alone, and I don’t need to share it with the handful of people who look at this space. The idea of converting these profound connections and experiences to simple “material” doesn’t sit right, and reading about all the fun little adventures I had in the streets of Fukuoka--the last stop of this trip--is probably not going to convince you of something you already know.

I will write about Fukuoka anyway, because this whole thing is for me:

The three of us are sitting in some park, somewhere, and it’s their first time having sake, so I figured it would be only right to make it an Ozeki One Cup, national drink of old men everywhere. I met them at a livehouse the night before, a young couple who works in the daytime to chase their music-making dreams at night. We instantly got along when I correctly identified his playing style to be heavily influenced by Arto Lindsay of the band DNA, and so we went out for drinks somewhere in Tenjin.

“So why did you come out all the way here?” they ask, just as I was asked in every part of my trip, and the further out I go the more concerned a voice it takes.

“I don’t know myself, either. But maybe it was just to meet you guys,” I said, and we all smiled at each other. The sake tastes gross, but that also makes it kinda fun.

We wander around the night and head into the various food stalls Fukuoka is famous for. We chat with people sitting to our left and right and enjoy whatever the old man running the spot puts out for us. We talk about music and creative dreams, and where we’re all heading. The world feels so, so large.

I know about Arto Lindsay because a friend of mine is a big fan of D2 for the Sega Dreamcast, which Arto contributed a song to. I played that game because of my friend, and then I researched Arto Lindsay who quickly became one of my favourite artists. The band he was in--DNA--was made up of himself, Robin Crutchfield, and a drummer named Ikue Mori. One time I saw Ikue Mori play in Tokyo with Yoshimi, the drummer of Boredoms, and Phew, an avant garde singer from the latter half of the 20th century.

In Fukuoka, we wander to a nightclub where by chance Phew will be doing a DJ set at exactly the moment we arrive, which is quite late at night. They both know who she is, and the three of us are so excited--we run inside. There’s Phew, playing a thick ambient set that can’t be danced to, and we just take it all in.

Before I know it the sun is rising and we’re saying goodbye, making all sorts of promises to see each other again when they eventually come to Tokyo. It’s a real long goodbye.

On the plane back, I forget to keep reading Buddha.

--

“There are a wide variety of characters and elements I introduced to the historical accounts of the Shakyamuni Buddha that are entirely devoid of historical fact,” writes Tezuka Osamu in a fairly clinical afterword in an attempt to make clear how much of Buddha’s story is fact and how much is fiction, which is quite a bit.

This is why the story of Siddartha as Tezuka writes it may as well be the truth itself, because it fulfills its task: that the reader understands on their own terms the value of a Buddhist line of thought. There may be some readers who feel the text is cheapened by the fact that so much of it is fictional, that it was something a person called Osamu Tezuka dreamed up and put to paper, in other words a “lie.” But I found myself at the end of all this no longer thinking about Siddartha, but Tezuka, who is a real historical figure. This is a person who is by and large responsible for the way entire industries work and how generations of artists have operated for decades. It would be irresponsible to say Tezuka alone is solely to credit for the larger anime and manga boom, but so would it to call Siddartha the sole proprietor of Buddhist thought.

Tezuka is someone who created a huge wave that ripples in ways the people who chase those dreams of becoming mangaka can barely even begin to understand, before they even know who a person called Osamu Tezuka is. Here I am half a century removed, and I’ve been led to this country because of those ripples in ways I barely understand, too, and probably came here to figure out.

The Buddha looks upon his humble servant Ananda, who asks him one last time what happens to humans after they die. Siddartha smiles and finds it almost cute that Ananda is still concerned about these things after so many years spent together, and compares life to a caterpillar becoming a butterfly: a completely natural process that is as transformative as it is unknowable to the creature it’s happening to. That perhaps one day we too will transcend our bodies and become something only knowable to those who have made that change, and completely incomprehensible to us. Ananda finds some kind of peace in the words spoken by the Buddha, near death himself.

One day all that will be left are the cocoons. It could be said that I worship the cocoons of people who have already passed, and if I really think about it this blog started because of how much of a disruption to my entire perception of myself and the world around me that the death of Takahashi Kazuki was. Whether it’s discussing Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in lectures halls or trying to solve deeply personal mysteries about card game manga on blogs written in a kind of manic desperation, the idea remains the same: that we are all trying to make sense of the waves of others insofar as they collide with our own.

---

The waves are really what this is all about, the so-called “tides of time.”

A lifetime ago my parents met as children at the summer homes of their parents in a more prosperous Turkey. The summer homes were right by the beach and my grandfathers all worked in the same industries, in the same small towns, in the same spheres. My parents met there, by the beach, their earliest memories together in the sand.

Once the waves of their lives led them back to each other as adults, they married and decided to have a child in landlocked Toronto, Ontario. The name for that child they eventually settled on was taken from those precious memories: the backdrop of it all, always there, always watching--the ocean, as it’s called in Turkish, became my name.

I didn’t like my name growing up. It was different from the other kids, which is something they let me know pretty much everyday of my life. Eventually I got older and started to appreciate that my name was unique, and had some kind of intensely personal meaning attached to it. Then I moved countries, and my name became this fractured thing pronounced and spelled differently based on who was saying it. At this point I’m not sure what I would consider the “proper” pronunciation to be, either.

I’ve also noticed as I continued to write this blog I would write many names of other people, or names of their work, or names of countries and their landmarks and so on, but never my own. I was hiding somewhere in the sentences, consciously refusing to write my own name into the stories that unfold here, even if they are all mine.

Maybe I liked Yugioh because it had a weird name, just like me. Maybe the whole point of this was to find the courage to be able to write my name out as it is: Deniz, the ocean.

The waves of my life led me across the ocean to the country called Japan where people like Osamu Tezuka put unseeable things into motion, just as I am probably doing now by putting myself out into the world, however small.

If you’re reading this, it means my waves have found you.

I’m right here. Where are you?

April 20th, 2025